How predictive is General Relativity?

Introduction

Einstein’s equations in vacuum, given by $R_{\mu \nu} = 0$, consist of ten coupled non-linear generic partial differential equations (PDEs) for the Lorentzian 4-metric tensor field, $g_{\mu \nu}(x)$. Given the complexity of these dynamical equations, it is not immediately clear that General Relativity (GR) is a deterministic theory.

Determinism is an important feature of physical theories. It implies that the whole past and future (the history) of a system can be evaluated, with infinite precision, from a minimal set of data. This makes deterministic theories extremely predictive, and thus appealing to the scientific framework.

Mathematically, determinism can be captured by a system of equations whose solutions exist, and can be uniquely determined. Usually, the system is differential with respect to some affine parameter (time), and the minimal set of data is the Cauchy (initial) data. Systems like these are said to be a well-posed Cauchy problem.

Examples in Physics are plenty: Newton’s 2nd Law, Newton’s Law of Gravitation, Maxwell’s equations, Schrödinger’s equation in the absence of measurements (collapses of the wave function), etc. Granted, these examples have much simpler dynamics than GR. Newton’s 2nd law and Schrödinger’s are ordinary differential equations. Newton’s Law of Gravitation and Maxwell’s are PDEs, but they are linear. Nonetheless, they reveal that what gives GR so much physical richness, is also what cripples its mathematical understanding, and possibly its predictability.

A detailed study of GR’s dynamics needs to address the proof of existence and uniqueness of its solutions. As mentioned, a natural step is to attempt to formulate a well-posed Cauchy problem for Einstein’s equations. However, this has proven to be difficult to do.

An important tool in this endeavor is the use of the harmonic gauge condition. In this gauge, Einstein’s equations assume the form of quasi-linear hyperbolic PDEs (wave-like equations). Choquet-Bruhat theorem then guarantees, at least, the local existence and uniqueness of solutions. In other words, GR is locally a well-posed Cauchy problem.

The Arnowitt-Deser-Misner (ADM) formalism plays a major role in clarifying Choquet-Bruhat’s results. But it also implies a particular choice of global spacetime foliation. This is a more restricted framework, applicable to only a subspace of solutions.

Finally, the global proof of existence and uniqueness is still an open problem in the mathematical-physics of GR. In fact, the theorems of existence of spacetime singularities, and the possible existence of Cauchy horizons indicate that a global proof might not exist. In other words, GR might not be a globally well-posed Cauchy problem.

The Weak and Strong Cosmic Censorship Conjectures (CCCs) were formulated in an attempt to mitigate this situation. Nevertheless, recent and old results are pilling up against their validity. One is then left wondering how predictive GR really is.

The harmonic gauge

GR has dynamics invariant under the group of diffeomorphisms among Lorentzian 4-manifolds. This means that its physical solutions are equivalence classes under these maps. Each class, or each physical solution, has many (actually, infinite) equivalent representatives. This enormous redundancy implies that Einstein’s equations are plagued with gauge artifacts, making them more complex than actually necessary to describe the physics of the gravitational field.

Gauge fixing these redundancies give us a way to simplify Einstein’s equations without sacrificing its physical content. A cleaver choice is the so-called harmonic gauge fixing conditions, defined by 4 constraint equations,

\[\Box x^{\mu} = 0 \;,\]where $\Box \equiv g^{\mu \nu} \nabla_{\mu} \nabla_{\nu}$ is the d’Alembertian differential operator.

Applying the harmonic gauge conditions to Einstein’s equations in vacuum shapes them into the form

\[\tilde{\Box} g_{\mu \nu} = N_{\mu \nu} \left( g, \partial g\right) \;,\]where $\tilde{\Box} \equiv g^{\mu\nu}\partial_{\mu}\partial_{\nu}$, and $N_{\mu \nu}$ is a smooth non-linear function up to the 1st derivative of $g_{\mu \nu}$. These are wave-like equations, mathematically classified as a set of 2nd order quasi-linear hyperbolic PDEs.

Luckily, the branch of Analysis dealing with quasi-linear hyperbolic PDEs is more developed than the one of fully non-linear generic PDEs. For instance, if $N_{\mu \nu}$ were to be analytic, then the local existence and uniqueness would automatically follow due to the so-called Cauchy-Kowalevski theorem. Unluckily, $N_{\mu \nu}$ is smooth but non-analytical in most physical situations.

In 1952, mathematical-physicist Yvonne Choquet-Bruhat managed to relax the analyticity condition via the use of Sobolev spaces (see a review by Yvonne herself). Her theorem was fully applicable to Einstein’s equation in the harmonic gauge, and thus guaranteed the local well-posedness of its Cauchy problem. In other words, Yvonne proved that GR has a deterministic evolution in a small enough neighborhood of its solution space.

The ADM formalism

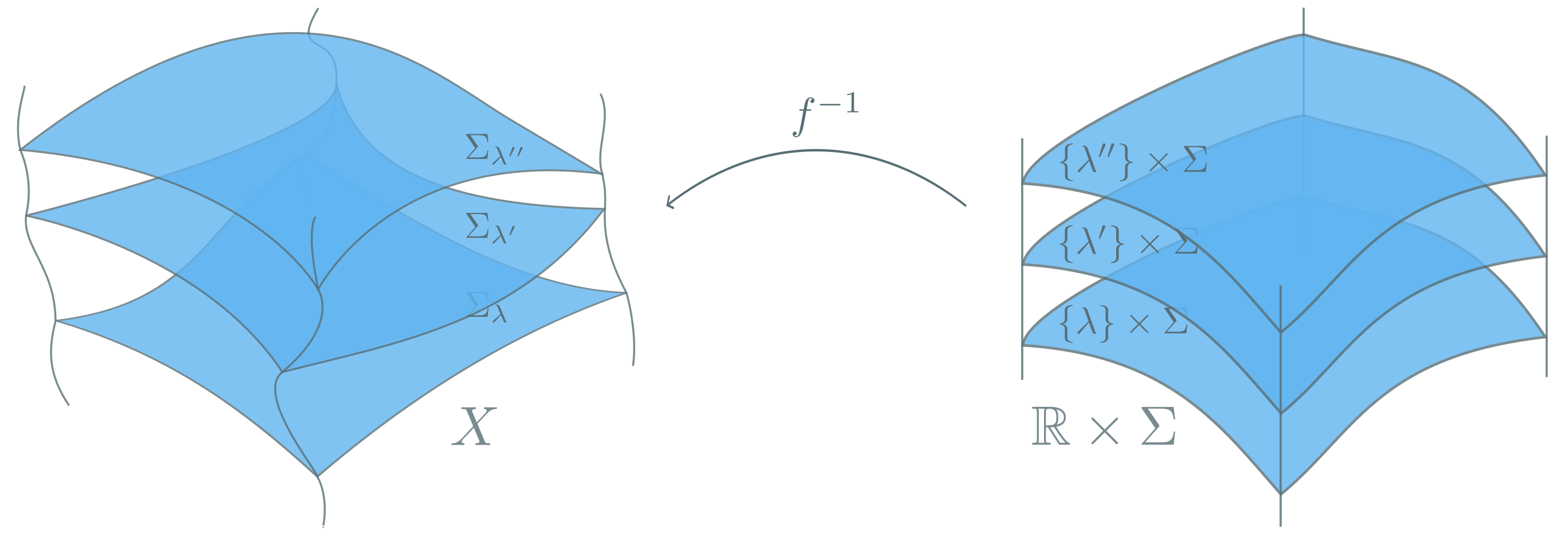

Let’s consider $\left(X, g_{\mu \nu}\right)$ a Lorentzian 4-manifold. If foliatable, there exists a diffeomorphism map $f: X \mapsto \mathbb{R}\times\Sigma$. This allows to define in $X$ a 1-parameter family of spacelike 3-manifolds, $\Sigma_{\lambda} \equiv {f}^{-1} \left(\left\{\lambda \right\} \times \Sigma \right) \; ; \; \lambda \in \mathbb{R}$, which are called the “leaves” in this foliation, check Figure 1.

Each leaf $\Sigma_{\lambda}$ has an induced 3-metric, $h_{ij} \left(\lambda\right)$, and an extrinsic curvature, $K_{ij} \left(\lambda\right)$. Furthermore, there also exists a globally well-defined, smooth, timelike vector field, $\partial_{\lambda}$, that generates a flow of time.

Foliability implies something very mundane for all of us: that space and time are separable, almost orthogonal entities. We measure space with a ruler, time with a clock. Not ever a situation arose in which we needed both a rule and a clock to measure space, or a ruler and a clock to measure time. And, to be frank, this is always true as long as we are measuring a small enough neighborhood of spacetime (most of us never even left Earth anyway).

In GR, however, foliability cannot always be guaranteed over the entire spacetime manifold (globally). Mind, this is a feature, not a bug, of GR’s full invariance under diffeomorphisms. Behind the scenes, the foliability condition actually selects solutions with partially broken invariance. A residual symmetry still exists on the leaves, but the breakage is just enough to allow a global notion of time, time evolution, initial data, etc. All welcomed ingredients for a well-posed Cauchy problem.

The ADM formalism uses the foliability condition to split Einstein’s equations apart. Mind, there are many (infinite) ways to split Einstein’s equations apart, but the ADM one is remarkable because, by projecting Einstein’s equations onto the leaves, ADM precisely separates them in constraint versus dynamical equations. Concurrently, it establishes the trio $\left( \Sigma_{\lambda}, h_{ij}, K_{ij}\right)$ as their Cauchy data.

The constraint equations

Not every Cauchy data $\left(\Sigma_{\lambda}, h_{ij}, K_{ij}\right)$ is compatible with a foliation of $\left(X, g_{\mu \nu}\right)$. The constraint equations exist to ensure this compatibility. Yvonne deduced these equations from energy estimates and properties of Sobolev spaces. But, using the ADM formalism, they naturally pop up as follows.

Let $\pi_{ij} \equiv 4 \pi \sqrt{h} \left( K_{ij} - h_{ij} K \right) \; ; \; K \equiv h^{ij}K_{ij} $ be the conjugated momenta of $h_{ij}$. Einstein’s equation, $R_{00} = 0$, when projected onto the leaves, $\Sigma_{\lambda}$, results in the now famous Hamiltonian constraint,

\[H = 0 \;,\]where $H \equiv - \sqrt{h} \left[ R^h + h^{-1} \left( \pi^{2} - \pi_{ij}\pi^{ij} \right) \right] \; ; \; \pi \equiv h^{ij}\pi_{ij}$, and $R^h$ is the curvature scalar of $h_{ij}$. On the other hand, when $R_{0i} = 0$ is projected onto $\Sigma_{\lambda}$, the result is the momentum constraint equations

\[P^i = 0 \;,\]where $P^i \equiv -2 \nabla_j \pi^{ij}$.

Together, the Hamiltonian and momentum constraints form a system of 4 PDEs that every Cauchy data for Einstein’s equations have to obey.

Here, we cannot avoid but mention that, in quantum gravity, these are the constraint equations that lead to the famous Wheeler-DeWitt equations,

\[\begin{aligned} \hat{H} \lvert \Psi \rangle &= 0 \;, \\ \hat{P}^i \lvert \Psi \rangle &= 0 \;, \end{aligned}\]for the quantum state $\lvert \Psi \rangle$ of the Universe. As well as to the problem of time, Ashtekar variables (a complex self-dual formulation of GR), and the loop representation of Carlo Rovelli and Lee Smolin, finally giving birth to Loop Quantum Gravity.

The dynamical ones

We discussed how Yvonne evolved her constrained set of Cauchy data via Einstein’s equations in the harmonic gauge. It turns out that the ADM formalism produces an even simpler description.

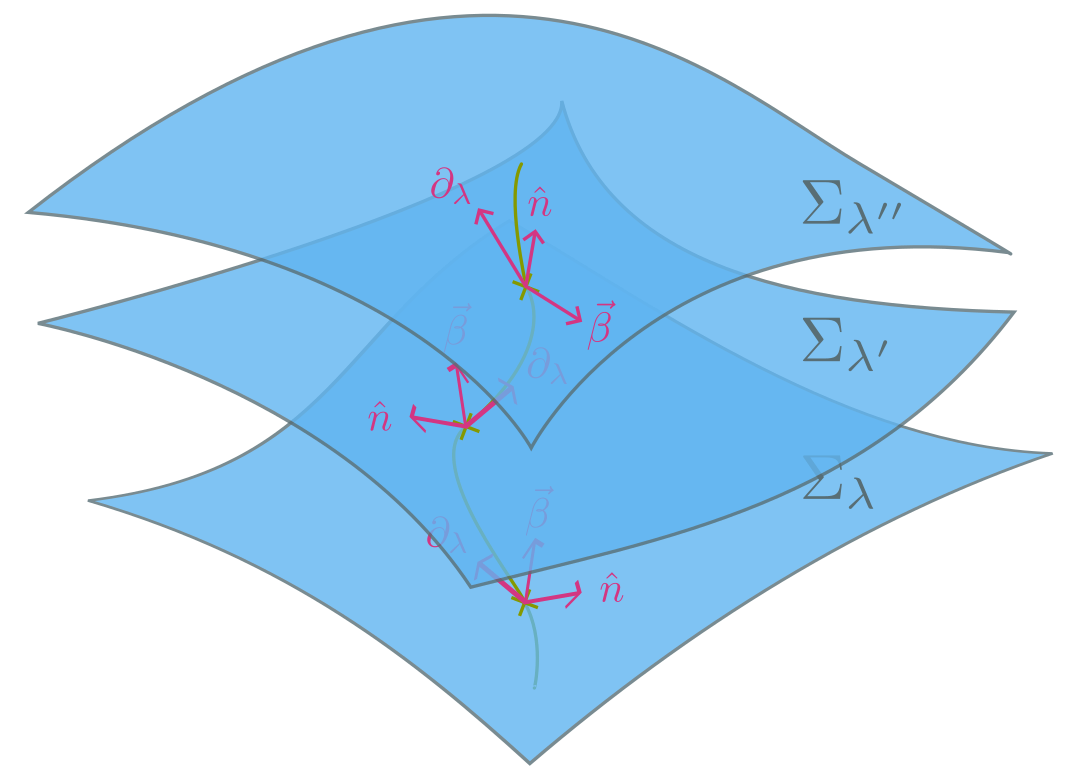

First, let us establish that the flow of time happens in the direction of the vector field $\partial_{\lambda} = \alpha \hat{n} + \vec{\beta}$, where $\alpha$ is the so-called lapse function, $\hat{n}$ is the unit vector normal to $\Sigma_{\lambda}$, and $\vec{\beta}$ the displacement vector implicitly given by the orthogonality condition $\hat{n} \cdot \vec{\beta} = 0$, see Figure 2.

The dynamical evolution of $h_{ij}$ can be obtained from the very definition of the extrinsic curvature. Explicitly, $K_{ij} \equiv - L_{\alpha \hat{n}} h_{ij} / 2$, where $L_{\alpha \hat{n}}$ is the Lie derivative along $\alpha\hat{n}$. Solving for $L_{\partial_{\lambda}} h_{ij}$, one arrives at

\[\partial_{\lambda} h_{ij} = - 2 K_{ij} + L_{\vec{\beta}} h_{ij} \;.\]This is a set of 10 quasi-linear 1st order PDEs, which give how the intrinsic local 3-geometry changes as we pass from one leaf, let’s say $\Sigma_{\lambda}$, to another infinitesimally close to it, let’s say $\Sigma_{\lambda + d\lambda}$.

On the other hand, the dynamical evolution for $K_{ij}$ is given by the projection of Einstein’s equations, $R_{ij} = 0$, onto the leaves. Explicitly,

\[\partial_{\lambda} K_{ij} = \alpha \left[ R_{ij}^h + K_{ij} K - 2 K_{ik} K_j^k \right] \;,\]where $R_{ij}^h$ is the Ricci tensor of $h_{ij}$. This is another set of 10 quasi-linear 1st order PDEs, which give how the local curvature, due to how the leaves “sit inside $X$”, changes within the infinitesimal time interval that separates $\Sigma_{\lambda}$ and $\Sigma_{\lambda + d\lambda}$.

Now, it is supposed to be clear that we can exchange Einstein’s equations in the harmonic gauge, used by Yvonne and given by 10 2nd order PDEs, with the 20 1st order PDEs in the ADM formulation. Surely, we now have double the equations to solve, but they are also way simpler. This is in full analogy with the passage from the Lagrangian to the Hamiltonian formulation of Classical Mechanics. Particularly how $n$ Euler-Lagrange equations becomes $2n$ Hamilton’s equations. In fact, one way to interpret the ADM formalism is as a Hamiltonian description of GR.

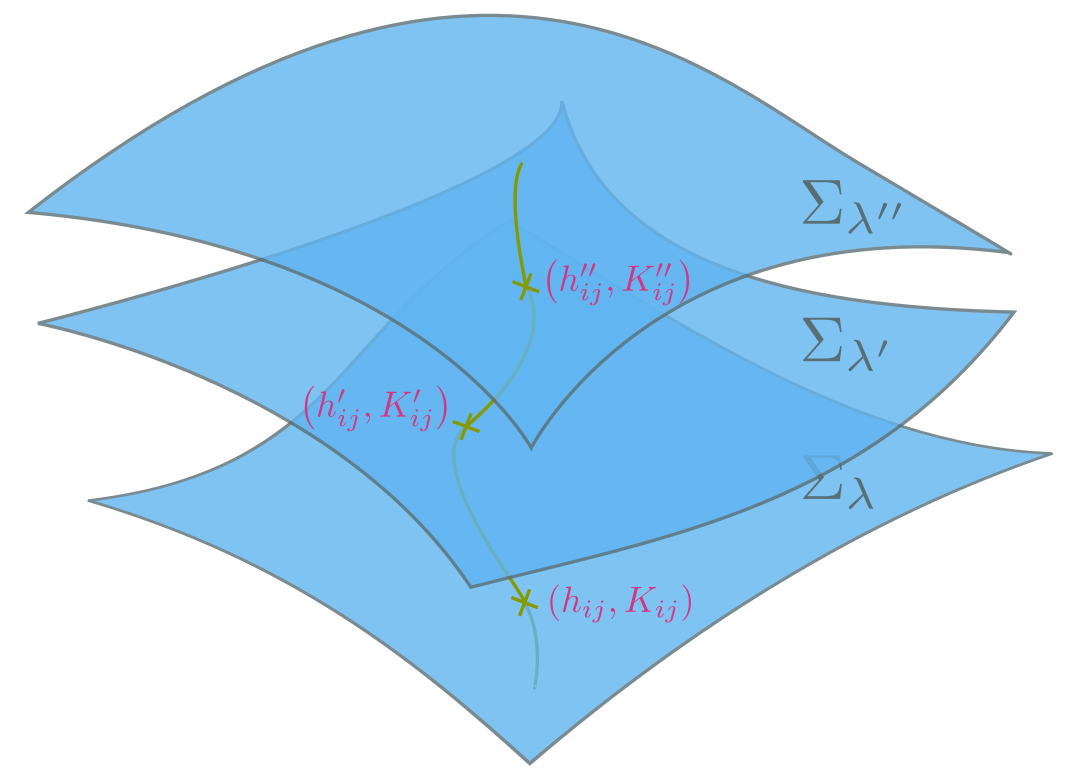

We stress that if GR is indeed fully deterministic, these dynamical equations can be used to evolve the Cauchy data $\left(\Sigma_{\lambda}, h_{ij}, K_{ij}\right)$ to ANY other leaf in the foliation, see Figure 3. This would be equivalent to know the entire plot of a movie from just a screenshot (unfortunately, not a rare occurrence these days). However, here the movie is the entire history of the Universe. This is what theoretical physicists and mathematicians mean when they speak of “a well-posed Cauchy problem for GR”.

Global well-posedness

Two milestones towards the global proof of existence of solutions are: i) the 1993 Christodoulou-Klainerman theorem and; ii) the 2003 Andersson-Moncrief theorem.

Result i) establishes the stability of Minkowski spacetime under small Cauchy data. In other words, the Minkowski solution exists for arbitrarily long periods of time and, solutions in its neighborhood tend to settle back towards it. This can also be interpreted as a theorem of non-existence of singularities in the space of solutions around Minkowski’s.

Result ii) is similar in spirit and technique to i). It establishes the future stability of hyperbolic cone spacetimes, also for small enough Cauchy data. These are compactified variants of the familiar $\kappa = -1$ FLRW cosmological solutions, admitting foliations of constant mean curvature, i.e., $\left\{\Sigma_{\lambda} \; ; \; K = \text{const.}\right\}$. The interpretation is analogous to the Minkowski’s case.

As one can see, though important, the above theorems cover only very localized areas in the space of all solutions. In fact, to this day, we still lack a theorem that ensures existence of arbitrary solutions to Einstein’s equations. Thus, we can already conclude that the global well-posedness represents a major open problem in the mathematical-physics of GR. For completeness, let’s now address the global uniqueness.

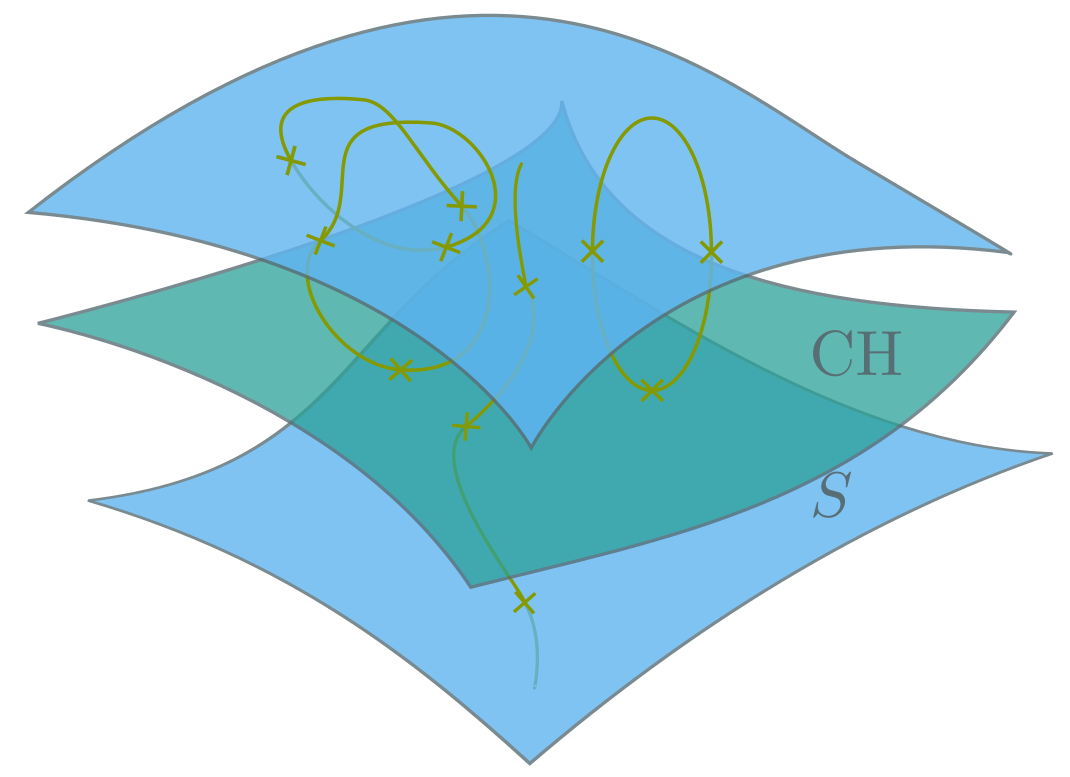

First, consider a differentiable timelike curve, $\gamma(\lambda) \; ; \; g \left(\gamma,\gamma\right) < 0$, which extends indefinitely to the past and to the future (also called inextensible). A Cauchy surface $S$ is a subset of $X$ punctured only once by every inextensible differentiable timelike curve in $X$. This has already being qualitatively depicted in Figure 3 for a single curve. The single point of intersection captures, in essence, the uniqueness of Cauchy data in each leaf.

Going back to the Choquet-Bruhat theorem, the local proof of uniqueness is in one-to-one correspondence with the existence of a Cauchy surface within the infinitesimal time interval $d \lambda$. In fact, one can always find a convenient local foliation in which every leaf is a Cauchy surface, also called a Cauchy foliation. Then, it is natural to expect that Yvonne’s theorem remains valid in a larger piece of spacetime as long as it admits a Cauchy foliation, like in Figure 3.

In 1969, Yvonne, now collaborating with Robert Geroch, developed the concept of a maximal globally hyperbolic developed (MGHD), and proved its uniqueness up to diffeomorphisms. This is the largest possible piece of spacetime that admits a Cauchy foliation. And, thus, for which Einstein’s equations imply a deterministic evolution. In particular, the Choquet-Bruhat-Geroch result represents a global uniqueness theorem for solutions diffeomorphic to a MGHD. These are called globally hyperbolic spacetimes.

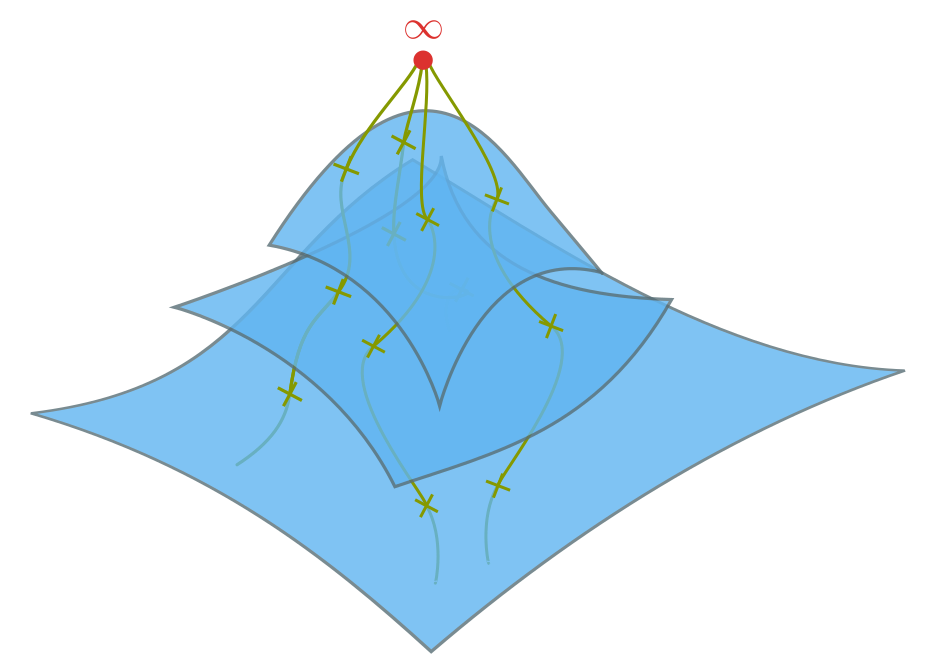

The expectation that the space of all solutions to Einstein’s equations contained exclusively globally hyperbolic spacetimes was, ironically, short-lived. By 1970, the Penrose-Hawking singularity theorems were fully developed. In the presence of spacetime singularities, inextensible differentiable timelike curves acquire finite proper time (they end). Thus, singularities represent boundaries for the MGHD. Additionally, they can spoil the global well-posedness in a number of other way, e.g., uniqueness can be broken by caustics (the focusing of geodesics into a single point), see Figure 4.

Penrose also very clearly defined the concept of Cauchy horizons (CHs). These are boundaries for the MGHD beyond which there are inextensible differentiable timelike curves that never punctured a Cauchy surface in the MGHD. In other words, a fragment of the movie that couldn’t be predicted from the initial snapshot.

CHs are inevitable when closed timelike curves (CTCs) are present, e.g., inside rotating black holes. CTC is just a fancy name for time travel. It breaks uniqueness by puncturing the would-be Cauchy surface many times over, see figure 5.

Clearly, all these results indicated the very real (and embarrassing) possibility that GR indeed is not a globally well-posed theory, i.e., it is not deterministic.

Cosmic Censorship Conjectures

The apparent ill-posedness of GR immediately bothered Penrose himself, making him conjecture that every singularity must be “hidden” inside an event horizon, known as the Weak Cosmic Censorship Conjecture (WCCC), and that Cauchy horizons are mathematical artifacts, unstable under metric perturbations. Thus, they could never survive gravitational collapse and form in Nature. This is known as the Strong Cosmic Censorship Conjecture (SCCC). If true, these conjectures would restore the deterministic nature of Einstein’s equations, even if only for infinitely far away (asymptotic) observers.

Since the 1970s, there was a strong expectation in the scientific community that Penrose’s CCCs would eventually be proven true. Indeed, since then, we struggled to find any natural process able to generate stable naked singularities (singularities not “dressed” by an event horizon). If they do exist, they are quite rare. In addition, there is mounting evidence that Cauchy horizons are inherently unstable if matter fields respect the Weak Energy Conditions (WECs).

So, how come, we are in the year 2025, and there is still no consensus in the scientific community about the real predictive power of GR? Well, the answer is, at least, 3-fold.

Firstly, we know since the 1990s that WCCC is mathematically false. Physicists P. S. Joshi, I. H. Dwivedi, D. Christodoulou, and others, have proven that naked singularities can form in specific cases through the collapse of matter. These results led famous physicist Stephen Hawking to concede his original bet against naked singularities. Indeed, GR appears to have no internal mechanism to prevent their formation.

The only caveat is that these examples heavily rely on a specific set of Cauchy data (e.g., with perfect spherical symmetry). Nonetheless, it might be only a matter of time until we figure out processes capable of generating them under very few assumptions, making naked singularities generic enough to occur in Nature.

Secondly, SCCC may not hold true when quantum effects are taken into account. Quantum fields do not always adhere to WECs, and quantum gravity effects may further complicate this discussion. Either of these factors could potentially stabilize the Cauchy horizon, making it long-lived.

Thirdly, and finally, SCCC has been proven mathematically false twice now, regardless of quantum effects. In 2003, M. Dafermos developed a proof of existence of the region across the CH inside charged (Reissner-Nordström) black holes. And, in 2017, Dafermos and J. Luk, managed to develop a similar proof for the CH inside rotating (Kerr) black holes.

The caveat is that these proofs hold only in the category of continuous spacetimes. The inherent instability of CHs when WECs are satisfied does not mean its interior region collapses out of existence into a singularity, as previously thought. Instead, in a much less dramatic manner, its smoothness ($C^\infty$ differentiability) collapses into just continuity ($C^0$). Black holes’ CHs, its interior region, and the metric field there survive the gravitational collapse but as continuous non-differentiable structures. Fair enough, if the metric is only $C^0$, then Einstein’s equations are not even valid there. And, once again, we are unable to draw further conclusions about their well-posedness.

Conclusions

GR’s situation looks grim at the moment. So much so, we are left to discuss sociological aspects of Physics.

Most physicists today have adopted the optimistic view that “GR is such a good theory that it predicts its own demise”. And, that its ultraviolet completion, whatever it is, will clarify the nature of singularities, Cauchy horizons, etc., ultimately reestablishing the global well-posedness of the spacetime evolution.

On the other hand, there is also the pessimistic (or realistic, depending on where you sit) branch. This branch takes these results at face value, and points out less singular alternatives to GR as paths forward. Additionally, it emphasizes that quantum gravity, something which we don’t agree on what it is even after +100 years of research, has no obligation to solve these issues. If it will, it’s anyone’s guess right now.

Personally, I sit fuzzily in the middle. I acknowledge the optimistic point of view, which might very well be the path forward. However, I also cannot help but sense a bit of biased effort to save GR. To spin the narrative, and turn a bug into a feature via marketing tactics. I do not particularly subscript to this aspect of the optimistic branch.

The pessimistic branch generally have good points. Alternatives to GR, sometimes for historical rather than scientific reasons, have been side lined. It immediately comes to my mind the Einstein-Cartan theory of gravity, which is capable of producing regular black holes and cosmological solutions, while fully agreeing with GR otherwise. However, I am also not convinced these alternatives are globally well-posed Cauchy problems. They tend to be less singular, yes, but singularities can still occur and global ill-posedness follows.

Ironically, it seems that the resolution of all these problems might lie in our future Cauchy development.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: